Price Realized £80,750 ($117,330)

Sale Information

Christie's Sale 6423

14 February 2001

London, King Street

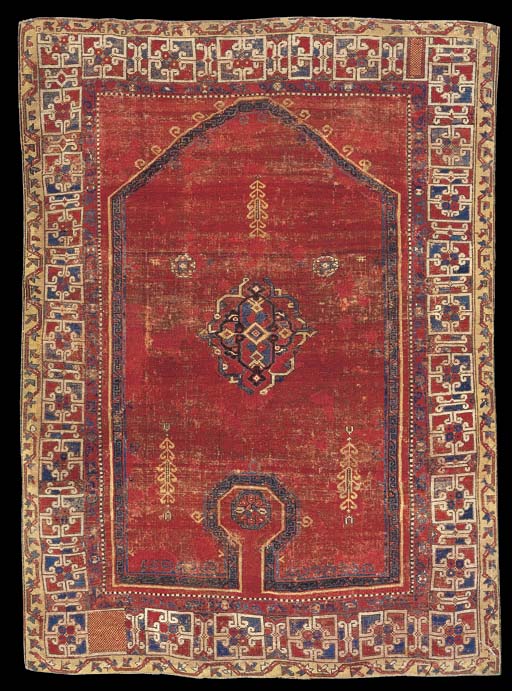

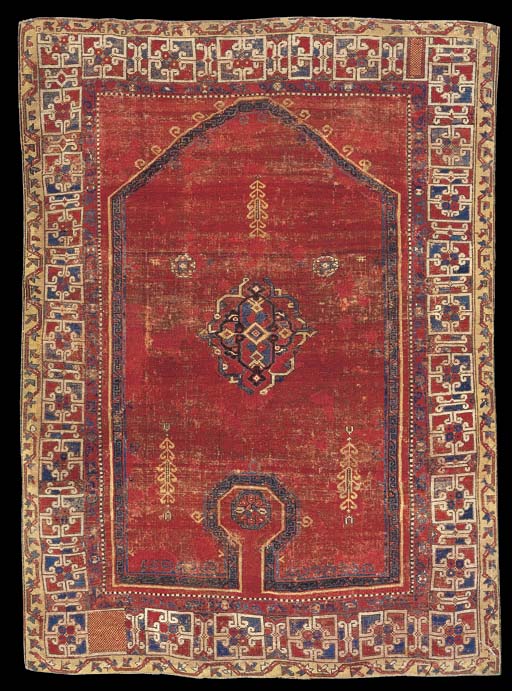

A "BELLINI" PRAYER RUG

WEST ANATOLIA, FIRST HALF 16TH CENTURY

The shaded brick-red field with a single flowerhead at one end around a

large brick red panel containing rosettes and hooked vine enclosing a

stylised palmette centrepiece, shaded medium blue linked S-motif inner frame

in a polychrome linked hooked panel border together with two densely

chequered panels at each end between golden yellow angular arrowhead meander,

brick red floral meander and barber-pole stripes, localised areas of wear

and restoration

5ft.6in. x 4ft.1in.(167cm. x 123cm.)

Provenance

Wher Collection, Switzerland

Literature

Eskenazi, J and Franses, M: Il Tappeto Orientale dal XV al XVII secolo,

Milan, 1982, no.6, pp.28-9 and 71.

Gantzhorn, Volkmar: The Christian Oriental Carpet, Cologne, 1991, ill.692,

p.498.

Mills, John: "Carpets in Paintings, The "Bellini", "Keyhole" or "Re-entrant"

Rugs", Hali 58, August 1991, pl.16, p.94

Lot Notes

Despite being depicted on a number of Italian paintings, there are very few

"re-entrant" prayer rugs which have survived from the early Ottoman period.

Of the surviving examples, in contrast to the small medallion Ushak rugs of

comparable date, there is great diversity. The present example is no

exception to this point; it contains a number of features not seen in any

others of the group.

The group is well discussed by John Mills, including the present rug as

noted above, illustrating all the early examples that he knew at the time,

but leaving out some mentioned by Johanna Zick which are only known from the

Erdmann archive (Zick, Johanna: "Eine Gruppe von Gebetsteppichen und ihre

Datierung", Berliner Museen, Berichte aus den ehem. preussischen

Kunstsammlunge, n.s., vol.11, pt.1, September 1961, pp.6-14). Despite his

concerns to the contrary, the article did not produce a flurry of further

examples; there remain less than twenty published examples, each of which

differs considerably from the others. Of all the others in the group, the

closest to the present rug is the magnificent example in Berlin (Spuhler,

Friedrich: Oriental Carpets in the Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin, London and

Boston, 1988, no.16, pp.37 and 159). Mills shows two paintings which can be

dated to the first decade of the sixteenth century which show rugs very

similar indeed to the Berlin rug. When discussing the present example, he

dates it slightly later on the basis of the rare border which is

occasionally found on Lotto rugs (Gantzhorn, op.cit, pl.398, p.279; Yetkin,

Serare: Historical Turkish Carpets, Istanbul, 1981, pl.32; Bernheimer Family

Collection of Carpets, Christie's London, 14 February 1996, lot 90 amongst a

few others). This border only appears on two paintings, one dateable to the

mid-16th century, the other to circa 1590 (Mills, op.cit, appendix, p.127).

There is also one rug which combines this border with the small-pattern

Holbein field (Kertesz-Badrus, Andrei: Türkische Teppiche in Siebenbürgen,

Bucharest, 1985, pl.2). One extra feature of the present border, not noted

in other versions, are the two panels of chequered motifs in opposite

corners. Were they just to fill gaps, there would be no reason for the

weaver to have woven a half-box in the upper border. Their symbolism however

is not clear.

The central medallion of this rug is remarkable. In contrast to the two main

forms and many minor variations on the small medallions seen in the Ushak

rugs, this lifts one element from the small-pattern Holbein design and uses

that as the focal point of the rug, complete with its very marked diagonal

colour symmetry, which is less appropriate when the element is removed from

the repeat pattern.

A number of authors have made suggestions about the symbolism of the

re-entrant design. One possibility suggested is that it is the innermost of

a complex design of niches. Another that it represents a pool of water,

comparable to the fountain at which the faithful can wash before praying in

mosques. Grant-Ellis, in his discussion of the battered example in

Philadelphia looks East, suggesting that it has a cosmologocal significance

similar to the mountain symbols at the bottom of Chinese ceremonial robes

and on a number of Chinese and East Turkestan rugs (Ellis, Charles Grant:

Oriental carpets, Phildelphia mUsuem of Art, Philadelphia, 1988, p.78). |

|